After EDSA: Historical Revisionism and Other Factors That Led to the Marcoses’ Return

- Posted on

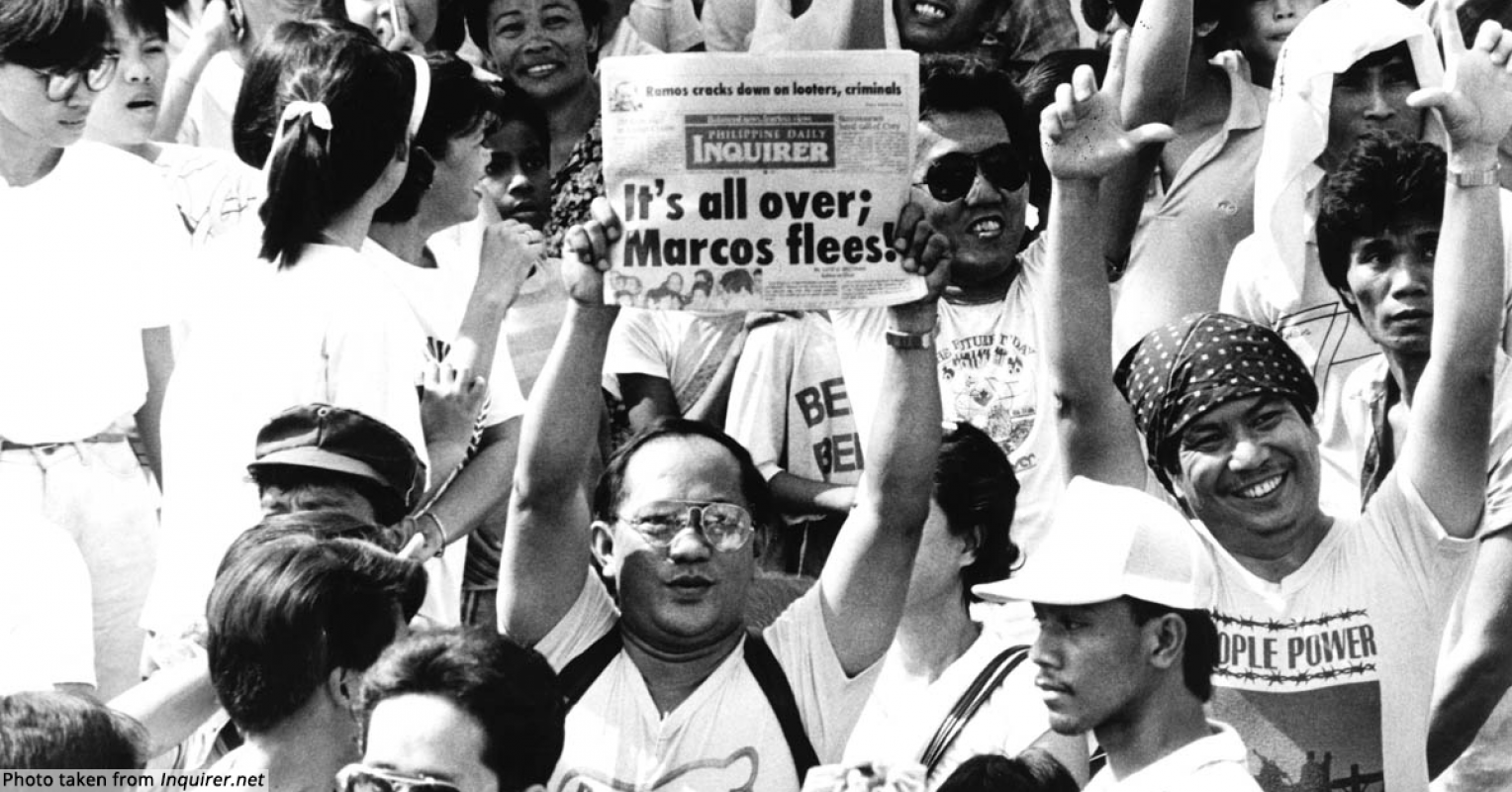

Thirty-five years since the Filipino people gathered along EDSA to oust the late dictator Ferdinand Marcos and his family, the Marcoses continue to make headlines, occupy positions of power, and have a strong presence in Philippine society. Their political clout is perhaps best exemplified by the results of the 2019 elections, which landed members of the Marcos family seats in the Senatorial, Congressional, provincial, and city levels. As former Rappler correspondent Carmela Fonbuena (2019) remarked in her report on said results, “[the] Marcoses have never had it this good in a long time.”

The infamous family’s ascent from exile to power has been partly attributed by both scholars and the general public to the phenomenon of “historical revisionism,” which arguably reached its peak during the highly disputed Marcos burial at the Libingan ng mga Bayani in 2016. Since then, the Marcoses, their supporters, and even government officials and entities have been repeatedly called out by the public for denying the atrocities committed by the Marcos regime, or worse, framing the dictator and his rule as praiseworthy. Most recently, on September 11, 2020, historical revisionism became a hot topic once more when #ArawNgMagnanakaw trended on Twitter after Congress approved a bill honoring the late dictator by declaring his birth anniversary a holiday in Ilocos Norte (Isinika, 2020). Netizens were outraged by the commemoration of a man whose rule is notorious for corruption and human rights violations.

In order to better understand historical revisionism and other factors that led to the once exiled family’s return to power, I spoke with University of the Philippines (UP) Diliman history professor Dr. Ferdinand C. Llanes. He shared with me his thoughts on the matter and what we, as a people, can still do to combat disinformation and promote good governance in the country.

Distortion and malicious denial

While the term “historical revisionism” has become largely pejorative, Dr. Llanes clarified that there is nothing inherently wrong with revising historical accounts. In fact, he emphasized that revision is a necessary endeavor when new information or witness accounts come to light. “Historians always revise as new facts or data present themselves,” he said. The type of revisionism that historians engage in aims to produce the most accurate accounts given all available information—a stark contrast with the way the term is often used today.

In its popular usage, Dr. Llanes noted that “historical revisionism” refers to the “distortion of the past as accepted by a considerable segment of the population, especially to suit a personal or political agenda.” This negative connotation has become closely associated with the Marcoses and martial law, he explained, because there are accepted truths and evidence that belie the former’s false claims on the Marcos regime.

For example, the Marcos siblings’ oft-repeated denial of the human rights violations and kleptocracy perpetrated by their father is disproved by court rulings both in the Philippines and abroad, years of probing by the Presidential Commission on Good Government (PCGG), and even Philippine law (VERA Files, 2018; VERA Files, 2020). Not long after their exile, U.S. courts found the Marcoses responsible for human rights abuses, including torture, summary execution, and disappearance, against thousands of Filipinos (Hilao v. Estate of Marcos, 1995; 1996). When they fled to Hawaii in 1986, the U.S. Customs found that they had brought with them jewelry worth around $5-10 million (Gwertzman, 1986) and cash amounting to $1.5 million or more than 30 million pesos, despite having declared only 2.4 million pesos upon their arrival (Lindsey, 1986). Contrary to claims by his supporters that Marcos holds a Guinness World Record for being the “Most Brilliant President in History” or “The Best President of All Time,” he actually earned a record for the “greatest robbery of a government”—one he holds to this day—due to his unexplained wealth estimated at $5-10 billion (Agence France-Presse, 2018; Rappler.com, 2021; Guinness World Records, n.d.; PCGG, n.d.). Marcos matriarch Imelda was also found guilty of seven counts of graft by the Sandiganbayan in 2018 (People v. Imelda Marcos, 2018). Even the law recognizes the human rights violations and plunder committed by the Marcoses when, under Section 7 of Republic Act No. 10368, otherwise known as the “Human Rights Victims Reparation and Recognition Act of 2013,” part of their recovered Swiss funds was designated as the source of monetary reparation for their victims. The list goes on.

“All of these things are on the record, witnessed by many people—many of whom are still alive. Even Marcos henchman Enrile was part of the [EDSA] revolt. How can you deny and suddenly change all that?,” asked Dr. Llanes. Yet, despite all the evidence on hand, the Marcoses’ crusade of disinformation and malicious denial continue to bear fruit, and it is not difficult to see why. Studies by researchers and journalists have revealed that their efforts to distort the past are longstanding, well-funded, and systematic, making use of print and online media, as well as heritage sites (Mendoza, 2019; Berdos, 2020).

Post-EDSA failings

There is no question that the Marcos family’s vast ill-gotten wealth helped them regain political power. After all, according to Dr. Llanes, “politics in the country is run by money.” It is also their wealth that allowed them to build and grow their disinformation network for decades. Apart from money, however, Dr. Llanes pointed to four post-EDSA failings as factors that paved the way for the Marcoses’ return: (1) the lack of a determined and effective prosecution of the Marcoses, (2) the absence of a legal prohibition against their return to public service, (3) poor voter education, and (4) the continued hold on power by the traditional political elite.

While numerous charges were filed against the Marcoses and their cronies after the revolution, few actually prospered; many were bogged down by long delays (Bueza, 2019). In fact, the recently decided case by the Sandiganbayan against Imelda Marcos in 2018 was filed back in 1991. Twenty-seven years after the case was instituted, the dictator’s wife was finally convicted, and the anti-graft court ordered the issuance of a warrant of arrest against her (Buan, 2018). Yet, in a move criticized and regarded by many as biased, the Philippine National Police refused to take her into custody on account of “old age” (Manglinong, 2018). She was ultimately allowed to post bail and is currently enjoying provisional liberty while appealing her conviction (Buan, 2018). The justice system and law enforcement in the Philippines are not known to invite the confidence of the people, and this case illustrates why. Dr. Llanes lamented the lack of justice for the victims of the Marcoses and the nation as a whole. “Walang problema mag-reconcile at mag-heal ang bayan. Okay ‘yun. Maganda ‘yun. But there must be a reckoning o pagtutuos,” he explained.

Not only was there no effective prosecution against the Marcoses, there was also no legal prohibition against their return to power. For instance, in the interest of democracy, “Guatemala’s constitution prohibits anyone who came to power by coup or force from running for president, and the same ban extends to their blood relatives up to the fourth degree of consanguinity” (Cuffe, 2019). Post-EDSA lawmakers and framers of the Constitution could have instituted a similar ban on holding office against members of the dictator’s family. Instead, almost immediately after they were permitted to return to the country, the Marcoses were allowed to run for office; Imelda even ran for president in 1992, just a year after her return (Rappler.com, 2017).

What is perhaps most alarming, however, is that many still welcomed and continue to welcome the Marcoses with open arms. As Dr. Llanes mentioned in his concluding remarks during the UP Day of Remembrance webinar on September 22, 2020, the nation failed to develop a “collective memory about the evils of martial law.” In our interview, he faulted the poor post-EDSA education in the country for “producing an electorate that is not alert to and critical of the track record of the Marcoses.” He shared that he himself reviewed history textbooks and found that many, even those produced during the Corazon Aquino administration, portrayed the dictator in a positive light, and there has been little improvement since then. In 2016, the youth group Anakbayan demanded the recall of a history textbook titled Lakbay ng Lahing Pilipino 5 which made it “[appear] that the series of floods and typhoons that resulted in less agricultural harvests and eventually protest rallies and rebel movements were the reasons for Marcos’ declaration of martial law” (Gonzales, 2016). Such erroneous information has remained unchecked over the years and, compounded by Marcos propaganda on social media, has significantly contributed to the people’s inadequacy in discerning historical distortions.

Finally, according to Dr. Llanes, an often glossed over factor that aided the Marcoses’ return is the fact that the same members of the Philippine elite stayed in power even after EDSA. Investigative journalist Malou Mangahas (2020) shared the same sentiment in her talk during the 2020 UP Day of Remembrance. “Our structures are weak. EDSA is not a revolution because there was no change; it is a mere revolt,” she said. To this day, the country remains dominated by a few members of the political elite, and there is danger in this, explained Dr. Llanes, because “members of the elite are prone to compromising with each other. Their politics is one of convenience, not of principle.”

The flip-flopping of some political butterflies, for instance, have served the Marcoses well in their attempt to distort the past. A good example of this is the ever-changing allegiance of Marcos crony-turned-rebel-turned-apologist Juan Ponce Enrile. Having served as Secretary of Justice and Minister of National Defense under the Marcos regime, Enrile was a prominent, if not the most prominent, Marcos crony before he withdrew his support for the regime in 1986. According to him, the Marcos camp cheated in the 1986 snap election, and he could no longer “serve a government that does not really represent the will of the people” (Enrile, 1986). Thirty years later, however, he would express support for the late dictator’s burial at the Libingan ng mga Bayani (Cepeda, 2016). Then, in 2018, Enrile would appear in a two-part interview with the dictator’s son Bongbong, extolling the late Marcos and denying the thousands of recorded political arrests, tortures, and killings he himself perpetuated as the architect of martial law (Viray, 2018; Guzman, 2018).

The power of the ballot

The years that followed the EDSA Revolution are rife with missed opportunities. Had the proper safeguards against the return of authoritarian figures been put in place, we might be confronting a different reality today. Still, not all hope is lost. As the 2022 Philippine election nears, the public need to be reminded of the power of the ballot and to be capacitated in determining the kind of public servants deserving to be voted into positions of governance.

As the 2022 Philippine election nears, the public need to be reminded of the power of the ballot and to be capacitated in determining the kind of public servants deserving to be voted into positions of governance.

“Right now, what can be done is to not elect them [the Marcoses], to stop their every move and attempt to return to power, and to educate people regarding martial law. This involves training teachers, correcting textbooks, etc. We have to have facts,” explained Dr. Llanes. Fortunately, he noted that many academics, especially historians, have stepped up to the challenge as the recent years have seen a flowering of publications on martial law, including a book he edited titled Tibak Rising: Activism in the Days of Martial Law, published in 2012 by Anvil Publishing, Inc. Beyond books and other print media, scholars and private individuals alike have also taken to the internet to combat the online disinformation perpetuated by the Marcoses (Limpin, 2021). As Dr. Llanes noted, “it [reconfiguring the past] is not as easy for them as there are those who answer back now. . . Social media, in itself, is not evil. In fact, it also gave progressives a platform to counter trolling by the Marcoses.”

Aside from educating the public on the ills of martial law, Dr. Llanes emphasized the importance of educating the electorate on “the criteria for good governance, even if Marcos is not mentioned.” According to him, this is an endeavor best accomplished “by existing political parties, which already have the resources to engage in voter education, rising above partisan interests to promote best voter practices and the highest moral standards in public service. Political education must necessarily include imparting the values of upholding human rights and integrity in public service.” While we still have a long way to go, Dr. Llanes believes that efforts to educate the masses not just about martial law and the Marcoses but also on good governance are not in vain. “I think it can make a dent; it can make inroads into a very corrupt political system.”

References

Agence France-Presse. (2018, November 20). Fact check: No, Ferdinand Marcos does not hold Guinness World Record for being the “world’s most brilliant president in history.” ABS-CBN News. https://news.abs-cbn.com/news/11/20/18/fact-check-no-ferdinand-marcos-does-not-hold-guinness-world-record-for-being-the-worlds-most-brilliant-president-in-history

Berdos, E. (2020, December 11). Propaganda web: Pro-Marcos literature, sites, and online disinformation linked. VERA Files. https://verafiles.org/articles/propaganda-web-pro-marcos-literature-sites-and-online-disinf

Buan, L. (2018, November 9). Imelda Marcos guilty of 7 counts of graft; court orders her arrest. Rappler. https://www.rappler.com/nation/imelda-marcos-guilty-of-graft-sandiganbayan-orders-arrest

Bueza, M. (2019, October 25). What’s the latest on cases vs Imelda Marcos, family? Rappler. https://www.rappler.com/newsbreak/in-depth/status-updates-rulings-court-cases-vs-marcos-family

Cepeda, M. (2016, August 22). Enrile supports hero’s burial for Marcos. Rappler. https://www.rappler.com/nation/enrile-supports-hero-burial-marcos

Cuffe, S. (2019, May 14). Guatemala ex-dictator’s daughter barred from presidential race. Aljazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/5/14/guatemala-ex-dictators-daughter-barred-from-presidential-race

Enrile, J.P. (1986). [Extract of the transcript of the February 22, 1986 press conference]. Official Gazette. https://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/1986/02/22/extract-of-the-transcript-of-press-conference-defense-minister-juan-ponce-enrile-and-deputy-chief-of-staff-fidel-v-ramos-on-various-matters/

Fonbuena, C. (2019, May 14). Marcoses take seats in Senate, Congress, province and city. Rappler. https://www.rappler.com/nation/elections/marcoses-take-seat-senate-congress-province-city-ilocos

Gonzales, Y.V. (2016, March 2). DepEd urged to recall textbooks with ‘misinformation’ on martial law. Inquirer.net. https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/770166/deped-urged-to-recall-textbooks-with-misinformation-on-martial-law

Guinness World Records. (n.d.). Greatest robbery of a government. Guinness World Records. https://www.guinnessworldrecords.com/world-records/65607-greatest-robbery-of-a-government

Guzman, R.C. (2018, September 21). 8 things Juan Ponce Enrile, Bongbong Marcos got wrong about martial law. CNN Philippines. https://cnnphilippines.com/news/2018/09/22/Bongbong-Marcos-Juan-Ponce-Enrile-martial-law-video-fact-check.html

Gwertzman, B. (1986, March 8). Marcos family jewelry brought to Hawaii is put at $5 million to $10 million. The New York Times, p. 6. https://www.nytimes.com/1986/03/08/world/marcos-family-jewelry-brought-to-hawaii-is-put-at-5-million-to-10-million.html

Hilao v. Estate of Marcos, MDL No. 840, C.A. No. 86-0390 (D. Haw. 1995). https://journals.upd.edu.ph/index.php/kasarinlan/article/download/5885/5248

Hilao v. Estate of Marcos, 103 F.3d 767 (9th Cir. 1996). https://law.utexas.edu/faculty/lmullenix/info/hilao_v_estate1996.pdf

Human Rights Victims Reparation and Recognition Act of 2013 s. 7. (Phil.).

Isinika, A. (2020, September 11). ‘Do not let revisionists win’: #ArawNgMagnanakaw trends on Marcos’ birthday. Rappler. https://www.rappler.com/nation/araw-ng-magnanakaw-trends-ferdinand-marcos-birthday

Llanes, F.C. (2020, September 22). Patunong People Power: “Turning points” [Webinar]. University of the Philippines. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ONQnpHTtcT8

Limpin, D. (2021). Pushing back against the lies: Efforts to fact-check the Marcoses on social media. Social Science Information, 47-48, pp. 9-13. https://pssc.org.ph/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/PSSC-SSI-Vol-47-48-2019-20.pdf

Lindsey, R. (1986, March 8). Ruling in Hawaii is Against Marcos. The New York Times, p. 6. https://www.nytimes.com/1986/03/08/world/ruling-in-hawaii-is-against-marcos.html

Mangahas, M. (2020, September 22). Patunong People Power: “Turning points” [Webinar]. University of the Philippines. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ONQnpHTtcT8

Manglinong, D. (2018, November 12). Old age? Health? The real reason why Imelda Marcos has yet to be arrested. Interaksyon. https://interaksyon.philstar.com/politics-issues/2018/11/12/137898/old-age-health-the-real-reason-why-imelda-marcos-has-yet-to-be-arrested/

Mendoza, G.B. (2019, November 20). Networked propaganda: How the Marcoses are using social media to reclaim Malacañang. Rappler. https://www.rappler.com/newsbreak/investigative/marcos-networked-propaganda-social-media

Mercado, N.A. (2020, September 2). House OKs bill declaring Sept. 11 ‘President Ferdinand Edralin Marcos Day’ in Ilocos Norte. Inquirer.net. https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1330379/house-oks-bill-declaring-sept-11-president-ferdinand-edralin-marcos-day-in-ilocos-norte

PCGG. (n.d.). Traces of Marcos Ill-gotten Wealth Abroad. Presidential Commission on Good Government [PCGG]. https://pcgg.gov.ph/traces-of-marcos-ill-gotten-wealth-abroad/

People of the Philippines v. Imelda Marcos, Crim Cases Nos. 17287-17291, 19225, 22867-22870 (2018). https://www.ombudsman.gov.ph/docs/05%20SB%20Decisions/SB-Crim-17287-17291%2C%2019225%20and%2022867-22870-People-of-the-Phils-vs-Marcos.pdf

Rappler.com. (2017, February 25). Timeline: How the Marcoses made their political comeback. Rappler. https://www.rappler.com/newsbreak/iq/timeline-marcos-political-comeback

Rappler.com. (2021, February 16). False: Guinness World Records names Marcos best president of all time. Rappler. https://www.rappler.com/newsbreak/fact-check/guinness-world-records-names-marcos-best-president-of-all-time

Reysio-Cruz, M. (2020, January 16). DepEd asked to review books’ depiction of martial law years. Inquirer.net. https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1213704/deped-asked-to-review-books-depiction-of-ml

VERA Files. (2018, October 19). Vera files fact check: Imee Marcos disclaimer on corruption during the Marcos regime is false. VERA Files. https://verafiles.org/articles/vera-files-fact-check-imee-marcos-disclaimer-corruption-duri

VERA Files. (2020, January 17). Vera files fact check: Bongbong Marcos falsely claims martial law horrors fabricated. VERA Files. https://verafiles.org/articles/vera-files-fact-check-bongbong-marcos-falsely-claims-martial

Viray, P.L. (2018, September 21). Fact-checking Enrile’s tete-a-tete with Bongbong Marcos. Philstar Global. https://www.philstar.com/headlines/2018/09/21/1853435/fact-checking-enriles-tete-tete-bongbong-marcos