READ: Dr. Lourdes Portus’ Synthesis of the Webinar on the Safety of Journalists in a Time of Crisis

- Posted on

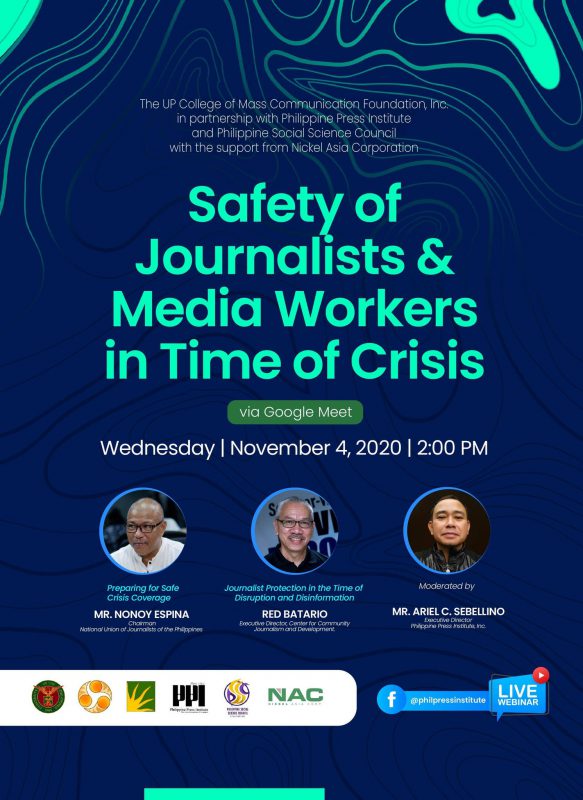

Read PSSC Executive Director Dr. Lourdes M. Portus’ synthesis of the webinar on the Safety of Journalists in a Time of Crisis held last November 4, 2020. You may watch the full webinar via the Philippine Press Institute’s Facebook page.

The webinar entitled “Safety of Journalists in a Time of Crisis” held this November has never been more timely—what with that tragic month of the so-called “Ampatuan Massacre” on November 23, 2009 still haunting many people’s thoughts, with no less than 53 people murdered and perished—majority of them, journalists—in Maguindanao’s Ampatuan territory.

Since that traumatic incident, general awareness and concern for the security of Philippine journalists and media workers have been in the forefront of the public’s consciousness and threat looms large in their professional practice.

And, now, here comes the present regime’s seeming penchant for “red-tagging” with the COVID-19 pandemic as the backdrop. This is, indeed, a virtual and multiple “whammy” for our country’s journalists and media workers.

There have been numerous discussions on the importance of “appropriate” and “timely” information, which is necessary in keeping the public safe and informed about what to do in times of crisis.

Media persons perform this function, in spite of dangers and threats to their own lives and those of their loved ones. However, it is sad to note that most media practitioners are underpaid; their welfare, neglected; and their safety—especially in high-risk situations—taken for granted. The media’s vulnerabilities have become even more evident during the current pandemic.

The webinar’s rationale, as gleaned from the concept paper written by the organizers, states the following:

A pandemic, at present, and an unfortunate incident, like the massacre, need a discourse that should bring to light, again, existing challenges vis-à-vis an agenda to prevent some misfortunes in the future.

The University of the Philippines – College of Mass Communication Foundation, Inc. (UP-CMCFI), in partnership with the Philippine Press Institute (PPI) and the Philippine Social Science Council (PSSC), organized the webinar, which featured, not only the lectures of two distinguished speakers but also breakout sessions that engaged participant-attendees in a workshop.

In her opening remarks, CMCFI President and webinar leader Dr. Arminda Santiago emphasized the historical importance of this webinar in that it would feature a workshop to deepen the discussion of and actively involve the participants. This is new, and the aim is to tweak the results of the webinar into something more concrete through the plans and recommendations that the workshop participants will proffer.

Meanwhile, Nickel Asia Corporation Vice President Mr. Jose Bayani Baylon’s message drumbeats the value of the media in society. They should be able to do what they do for the public to get the facts. They should have a safe environment in order to fulfill their role in society.

The Executive Director of the CMCFI, Ms. Rissa Silvestre, followed by giving a bird’s-eye view of what the participants can expect from the webinar.

The webinar then proceeded to the presentation of Mr. Jose Jaime L. Espina, the Chair of the National Union of Journalists of the Philippines (NUJP), a safety trainer and peer supporter, and a journalist for more than 30 years. He tackled the topic Safely Covered: Preparing for Safe Crisis Coverage.

Mr. Espina’s talk concluded with the following statement: “By failing to prepare, you are preparing to fail.” This says it all—a succinct message that applies not only to journalists and media workers but to everyone else as well.

Giving context in his talk, Mr. Espina first defined what “crisis” is, settling on a catch-all definition: a “time of intense difficulty or danger.” And, in a crisis situation, he emphasized four roles that the media normally play: to inform, to communicate, to give early warnings, and to conduct community fora.

He underscored the necessity of preparing and having a Disaster Response Plan (DRP), which should be a workshop-output and which should also involve all stakeholders in one’s own department or office. The DRP’s usefulness lies in people being able to determine whom to call and deploy first and help pre-assign tasks for contingencies.

The speaker advised the audience to prepare for a worst-case scenario, wherein the newsroom may virtually be rendered unreachable. It would be best to possess more than one cellphone, have secured hard drives with critical files, have a list of contacts and have back-up partners, like local universities or colleges, or other news organizations. Back-ups may include Facebook and Twitter or even mobile messaging. For personal safety, he gave the audience a “to-do” list and a set of questions to evaluate the risk situation.

An important item, which everybody should have, is the “go bag” containing the essentials—gadgets, food, clothes, toiletries, radio, batteries and other necessities, including a copy of the emergency plan.

More importantly, something that is good for mental health, Mr. Espina accentuated, is having a good attitude during crises, like embracing stress and trauma as real occupational hazards and not as weaknesses. There should be mutual care among colleagues, awareness of any previous traumatic experience, and constant contact with personnel in the field and their families.

What followed was the presentation of Dir. Red Batario, the Executive Director of the Center for Community Journalism and Development, Inc. (CCJDI) on Journalist Protection in the Time of Disruption and Disinformation.

His talk was prefaced by the current issue on the red-tagging of journalists. He then reminded the audience of the existence of a “Philippine Plan of Action on the Safety of Journalists,” which is based on the “United Nations Plan of Action on the Safety of Journalists” and the “Issue of Impunity.” The Philippine plan promotes the safety and protection of journalists and other media workers and pursues the safeguarding of press freedom. What is unique and impressive about this plan is the process of its development—inclusive, participatory, and multi-stakeholder-driven. The actions, insights, and recommendations from media, government, the academe, and civil society sectors were generated during multi-stakeholder consultations at the regional and national levels. The plan had emerged from dialogues with state security forces, as well as training sessions on journalists’ safety, with the Journalists Safety Association Group (JSAG) providing directions in its completion.

Mr. Batario then discussed the action plan for four flagship areas, namely: a) “Integrity and Professionalism”; b) “Conducive Working Conditions”; c) “Safety and Protection Mechanisms”; d) “Criminal Justice System and Public Information, Journalism Education, and Research.”

Said flagship areas practically cover a whole gamut of safety nets, along with key action points (short-, medium-, and long-term) and ethical standards and professionalism, in the practice of journalism and media work. These also include occupational safety, strengthening the response to attacks and threats, gender sensitivity, the examination of laws like the anti-terrorism law, the prosecution process, and media information literacy.

Open Forum

After both presentations of Chair Espina and Dir. Batario, the Open Forum session ensued with various concerns being raised on the safety of journalists and ably addressed by the speakers. The following were the questions posed in the chat box and Facebook pages of CMCFI, PPI, and PSSC with the respective responses of the speakers:

- On the question of whether or not journalists should be armed, both speakers said that they respect individuals’ rights to arm themselves but they do not promote and encourage gun use because they will be marked as combatants, and both speakers do not want the development of a gun culture. An opposing stand was shared by one of the audience members—that journalists should arm and protect themselves, provided they are educated on when and how to use a gun—as he was of the opinion that journalists should not be sitting ducks.

- The second question was about some editors being oblivious as to the safety and care of journalists involved in risky coverage. The speakers said that concern for personal safety is valid and should be considered.

- The next question was about safety from red-tagging. Accordingly, there is no one answer to this, but journalists should ensure the integrity and accuracy of their stories and should gain the trust of the citizens. They should also coordinate with human rights groups and have a united front against red-tagging.

- The fourth question was about ways of strengthening Media Information Literacy (MIL). There should be focus on integrating journalism courses in the academe, but this should go beyond schools. It should also trickle down to common folks who read newspapers and watch or listen to the news.

- The last point was not a question but a comment to always maintain ethical standards in writing.

Workshop

After the Open Forum, the webinar proceeded to its high point—the workshop, with 27 participants divided into two groups. These workshop participants came from PPI’s members, who represent community newspapers, radio stations, the print sector, and other platforms nationwide.

Under the supervision of two seasoned facilitators, namely, CMC Associate Dean Dr. Rachel Khan and CMC Journalism Department Chair Lynda Garcia, each group of participants discussed the following questions posed by the speakers:

- Chair Espina:

- Have you covered a crisis? Please share your experience on how you prepared and how your newsroom supported you.

- Check your phonebooks. Do you have one? How many emergency numbers are stored in your phonebook?

- Do you know at least two of your editors who live closes to your newsrooms? How close are they?

- Director Batario:

- What is the biggest threat facing you today as a journalist?

- How can you and the journalism community address that threat?

The workshop results were subsequently presented in the plenary as follows:

Group 1: Director Batario and Chair Garcia

Have you covered a crisis? Please share your experience on how you prepared and how your newsroom supported you.

| Crisis | Preparation | Newsroom Support | |

| Participant 1 | Typhoon Rolly | Approached LGUs, prepared a go bag | Logistics, food, equipment |

| Participant 2 | – | Not prepared | – |

| Participant 3 | Typhoon Peping (2008), Typhoon Cosme (2012) |

Peping: Waited for the water level to subside to a manageable level Cosme: Preparation was possible because of PAGASA reports; proper equipment were brought |

Moral support |

| Participant 4 | Earthquakes in Mindanao | Apart from duck, cover, and hold, not much preparation given the unexpected nature of earthquakes | Monitored safety through frequent calls |

Check your phonebooks. Do you have one? How many emergency numbers are stored in your phonebook?

| Emergency Contacts | |

| Participant 1 | 48 municipal and city police stations, 5 DRRMOs, father |

| Participant 2 | 1 provincial government, 3 police stations, 2 DRRMOs |

| Participant 3 | 14 provincial hospitals |

| Participant 4 | 50 municipal police stations, NGCP, MDRRMC |

| Participant 5 | district police stations in Metro Manila, hospitals NDRRMC, Red Cross, MMDA, wife |

Do you know at least two of your editors who live closes to your newsrooms? How close are they?

Two participants responded affirmatively, with the closest editors living approximately 15 and 30 minutes from their newsrooms.

Group 2: Chair Espina and Dr. Khan

What is the biggest threat facing you today as a journalist?

The group pointed out that the threats to journalists are not limited to physical danger due to coverage. Nonphysical threats include:

- Lack of job security – Many lost their jobs during this period due to the lack of sustainability of print media during the pandemic and the closure of ABS-CBN, which affected correspondents in the provinces.

- Lack of transparency of the government, especially LGUs

- Threats by politicians, especially in the form of libel charges

- Mental health problems and trauma from covering the pandemic and disasters

- Disinformation and how the media themselves are sometimes misled, especially during disasters

- Lack of logistical support from the community and the government, especially in terms of the sustainability of media establishments

How can you and the journalism community address that threat?

The group suggested community action in the form of the following:

- There is a need for journalists to learn how to protect themselves.

- Fact-checking should be a practice among journalists, not just official fact-checkers. Journalists should not let our guard down even when the news comes from their inner circle as they can also fall victim to false information.

- There is a need to assess what newsrooms are doing for their staff in terms of protection (e.g., PPEs in covering the pandemic, hazard pay, protection from harassment by the powers-that-be).

- There should be constant sharing (of experiences and best practices) and support from the media community, especially when one is facing threats. Webinars like this help keep community journalists informed of the situations of their fellow journalists.

The webinar then ended with the closing remarks of Dr. Elena Pernia, Vice President for Public Affairs of the UP System and former Dean of the College of Mass Communication.

Read PSSC Executive Director Dr. Lourdes M. Portus’ synthesis of the webinar on the Safety of Journalists in a Time of Crisis held last November 4, 2020. You may watch the full webinar via the Philippine Press Institute’s Facebook page.

The webinar entitled “Safety of Journalists in a Time of Crisis” held this November has never been more timely—what with that tragic month of the so-called “Ampatuan Massacre” on November 23, 2009 still haunting many people’s thoughts, with no less than 53 people murdered and perished—majority of them, journalists—in Maguindanao’s Ampatuan territory.

Since that traumatic incident, general awareness and concern for the security of Philippine journalists and media workers have been in the forefront of the public’s consciousness and threat looms large in their professional practice.

And, now, here comes the present regime’s seeming penchant for “red-tagging” with the COVID-19 pandemic as the backdrop. This is, indeed, a virtual and multiple “whammy” for our country’s journalists and media workers.

There have been numerous discussions on the importance of “appropriate” and “timely” information, which is necessary in keeping the public safe and informed about what to do in times of crisis.

Media persons perform this function, in spite of dangers and threats to their own lives and those of their loved ones. However, it is sad to note that most media practitioners are underpaid; their welfare, neglected; and their safety—especially in high-risk situations—taken for granted. The media’s vulnerabilities have become even more evident during the current pandemic.

The webinar’s rationale, as gleaned from the concept paper written by the organizers, states the following:

A pandemic, at present, and an unfortunate incident, like the massacre, need a discourse that should bring to light, again, existing challenges vis-à-vis an agenda to prevent some misfortunes in the future.

The University of the Philippines – College of Mass Communication Foundation, Inc. (UP-CMCFI), in partnership with the Philippine Press Institute (PPI) and the Philippine Social Science Council (PSSC), organized the webinar, which featured, not only the lectures of two distinguished speakers but also breakout sessions that engaged participant-attendees in a workshop.

In her opening remarks, CMCFI President and webinar leader Dr. Arminda Santiago emphasized the historical importance of this webinar in that it would feature a workshop to deepen the discussion of and actively involve the participants. This is new, and the aim is to tweak the results of the webinar into something more concrete through the plans and recommendations that the workshop participants will proffer.

Meanwhile, Nickel Asia Corporation Vice President Mr. Jose Bayani Baylon’s message drumbeats the value of the media in society. They should be able to do what they do for the public to get the facts. They should have a safe environment in order to fulfill their role in society.

The Executive Director of the CMCFI, Ms. Rissa Silvestre, followed by giving a bird’s-eye view of what the participants can expect from the webinar.

The webinar then proceeded to the presentation of Mr. Jose Jaime L. Espina, the Chair of the National Union of Journalists of the Philippines (NUJP), a safety trainer and peer supporter, and a journalist for more than 30 years. He tackled the topic Safely Covered: Preparing for Safe Crisis Coverage.

Mr. Espina’s talk concluded with the following statement: “By failing to prepare, you are preparing to fail.” This says it all—a succinct message that applies not only to journalists and media workers but to everyone else as well.

Giving context in his talk, Mr. Espina first defined what “crisis” is, settling on a catch-all definition: a “time of intense difficulty or danger.” And, in a crisis situation, he emphasized four roles that the media normally play: to inform, to communicate, to give early warnings, and to conduct community fora.

He underscored the necessity of preparing and having a Disaster Response Plan (DRP), which should be a workshop-output and which should also involve all stakeholders in one’s own department or office. The DRP’s usefulness lies in people being able to determine whom to call and deploy first and help pre-assign tasks for contingencies.

The speaker advised the audience to prepare for a worst-case scenario, wherein the newsroom may virtually be rendered unreachable. It would be best to possess more than one cellphone, have secured hard drives with critical files, have a list of contacts and have back-up partners, like local universities or colleges, or other news organizations. Back-ups may include Facebook and Twitter or even mobile messaging. For personal safety, he gave the audience a “to-do” list and a set of questions to evaluate the risk situation.

An important item, which everybody should have, is the “go bag” containing the essentials—gadgets, food, clothes, toiletries, radio, batteries and other necessities, including a copy of the emergency plan.

More importantly, something that is good for mental health, Mr. Espina accentuated, is having a good attitude during crises, like embracing stress and trauma as real occupational hazards and not as weaknesses. There should be mutual care among colleagues, awareness of any previous traumatic experience, and constant contact with personnel in the field and their families.

What followed was the presentation of Dir. Red Batario, the Executive Director of the Center for Community Journalism and Development, Inc. (CCJDI) on Journalist Protection in the Time of Disruption and Disinformation.

His talk was prefaced by the current issue on the red-tagging of journalists. He then reminded the audience of the existence of a “Philippine Plan of Action on the Safety of Journalists,” which is based on the “United Nations Plan of Action on the Safety of Journalists” and the “Issue of Impunity.” The Philippine plan promotes the safety and protection of journalists and other media workers and pursues the safeguarding of press freedom. What is unique and impressive about this plan is the process of its development—inclusive, participatory, and multi-stakeholder-driven. The actions, insights, and recommendations from media, government, the academe, and civil society sectors were generated during multi-stakeholder consultations at the regional and national levels. The plan had emerged from dialogues with state security forces, as well as training sessions on journalists’ safety, with the Journalists Safety Association Group (JSAG) providing directions in its completion.

Mr. Batario then discussed the action plan for four flagship areas, namely: a) “Integrity and Professionalism”; b) “Conducive Working Conditions”; c) “Safety and Protection Mechanisms”; d) “Criminal Justice System and Public Information, Journalism Education, and Research.”

Said flagship areas practically cover a whole gamut of safety nets, along with key action points (short-, medium-, and long-term) and ethical standards and professionalism, in the practice of journalism and media work. These also include occupational safety, strengthening the response to attacks and threats, gender sensitivity, the examination of laws like the anti-terrorism law, the prosecution process, and media information literacy.

Open Forum

After both presentations of Chair Espina and Dir. Batario, the Open Forum session ensued with various concerns being raised on the safety of journalists and ably addressed by the speakers. The following were the questions posed in the chat box and Facebook pages of CMCFI, PPI, and PSSC with the respective responses of the speakers:

- On the question of whether or not journalists should be armed, both speakers said that they respect individuals’ rights to arm themselves but they do not promote and encourage gun use because they will be marked as combatants, and both speakers do not want the development of a gun culture. An opposing stand was shared by one of the audience members—that journalists should arm and protect themselves, provided they are educated on when and how to use a gun—as he was of the opinion that journalists should not be sitting ducks.

- The second question was about some editors being oblivious as to the safety and care of journalists involved in risky coverage. The speakers said that concern for personal safety is valid and should be considered.

- The next question was about safety from red-tagging. Accordingly, there is no one answer to this, but journalists should ensure the integrity and accuracy of their stories and should gain the trust of the citizens. They should also coordinate with human rights groups and have a united front against red-tagging.

- The fourth question was about ways of strengthening Media Information Literacy (MIL). There should be focus on integrating journalism courses in the academe, but this should go beyond schools. It should also trickle down to common folks who read newspapers and watch or listen to the news.

- The last point was not a question but a comment to always maintain ethical standards in writing.

Workshop

After the Open Forum, the webinar proceeded to its high point—the workshop, with 27 participants divided into two groups. These workshop participants came from PPI’s members, who represent community newspapers, radio stations, the print sector, and other platforms nationwide.

Under the supervision of two seasoned facilitators, namely, CMC Associate Dean Dr. Rachel Khan and CMC Journalism Department Chair Lynda Garcia, each group of participants discussed the following questions posed by the speakers:

- Chair Espina:

- Have you covered a crisis? Please share your experience on how you prepared and how your newsroom supported you.

- Check your phonebooks. Do you have one? How many emergency numbers are stored in your phonebook?

- Do you know at least two of your editors who live closes to your newsrooms? How close are they?

- Director Batario:

- What is the biggest threat facing you today as a journalist?

- How can you and the journalism community address that threat?

The workshop results were subsequently presented in the plenary as follows:

Group 1: Director Batario and Chair Garcia

Have you covered a crisis? Please share your experience on how you prepared and how your newsroom supported you.

| Crisis | Preparation | Newsroom Support | |

| Participant 1 | Typhoon Rolly | Approached LGUs, prepared a go bag | Logistics, food, equipment |

| Participant 2 | – | Not prepared | – |

| Participant 3 | Typhoon Peping (2008), Typhoon Cosme (2012) |

Peping: Waited for the water level to subside to a manageable level Cosme: Preparation was possible because of PAGASA reports; proper equipment were brought |

Moral support |

| Participant 4 | Earthquakes in Mindanao | Apart from duck, cover, and hold, not much preparation given the unexpected nature of earthquakes | Monitored safety through frequent calls |

Check your phonebooks. Do you have one? How many emergency numbers are stored in your phonebook?

| Emergency Contacts | |

| Participant 1 | 48 municipal and city police stations, 5 DRRMOs, father |

| Participant 2 | 1 provincial government, 3 police stations, 2 DRRMOs |

| Participant 3 | 14 provincial hospitals |

| Participant 4 | 50 municipal police stations, NGCP, MDRRMC |

| Participant 5 | district police stations in Metro Manila, hospitals NDRRMC, Red Cross, MMDA, wife |

Do you know at least two of your editors who live closes to your newsrooms? How close are they?

Two participants responded affirmatively, with the closest editors living approximately 15 and 30 minutes from their newsrooms.

Group 2: Chair Espina and Dr. Khan

What is the biggest threat facing you today as a journalist?

The group pointed out that the threats to journalists are not limited to physical danger due to coverage. Nonphysical threats include:

- Lack of job security – Many lost their jobs during this period due to the lack of sustainability of print media during the pandemic and the closure of ABS-CBN, which affected correspondents in the provinces.

- Lack of transparency of the government, especially LGUs

- Threats by politicians, especially in the form of libel charges

- Mental health problems and trauma from covering the pandemic and disasters

- Disinformation and how the media themselves are sometimes misled, especially during disasters

- Lack of logistical support from the community and the government, especially in terms of the sustainability of media establishments

How can you and the journalism community address that threat?

The group suggested community action in the form of the following:

- There is a need for journalists to learn how to protect themselves.

- Fact-checking should be a practice among journalists, not just official fact-checkers. Journalists should not let our guard down even when the news comes from their inner circle as they can also fall victim to false information.

- There is a need to assess what newsrooms are doing for their staff in terms of protection (e.g., PPEs in covering the pandemic, hazard pay, protection from harassment by the powers-that-be).

- There should be constant sharing (of experiences and best practices) and support from the media community, especially when one is facing threats. Webinars like this help keep community journalists informed of the situations of their fellow journalists.

The webinar then ended with the closing remarks of Dr. Elena Pernia, Vice President for Public Affairs of the UP System and former Dean of the College of Mass Communication.

Read PSSC Executive Director Dr. Lourdes M. Portus’ synthesis of the webinar on the Safety of Journalists in a Time of Crisis held last November 4, 2020. You may watch the full webinar via the Philippine Press Institute’s Facebook page.

The webinar entitled “Safety of Journalists in a Time of Crisis” held this November has never been more timely—what with that tragic month of the so-called “Ampatuan Massacre” on November 23, 2009 still haunting many people’s thoughts, with no less than 53 people murdered and perished—majority of them, journalists—in Maguindanao’s Ampatuan territory.

Since that traumatic incident, general awareness and concern for the security of Philippine journalists and media workers have been in the forefront of the public’s consciousness and threat looms large in their professional practice.

And, now, here comes the present regime’s seeming penchant for “red-tagging” with the COVID-19 pandemic as the backdrop. This is, indeed, a virtual and multiple “whammy” for our country’s journalists and media workers.

There have been numerous discussions on the importance of “appropriate” and “timely” information, which is necessary in keeping the public safe and informed about what to do in times of crisis.

Media persons perform this function, in spite of dangers and threats to their own lives and those of their loved ones. However, it is sad to note that most media practitioners are underpaid; their welfare, neglected; and their safety—especially in high-risk situations—taken for granted. The media’s vulnerabilities have become even more evident during the current pandemic.

The webinar’s rationale, as gleaned from the concept paper written by the organizers, states the following:

A pandemic, at present, and an unfortunate incident, like the massacre, need a discourse that should bring to light, again, existing challenges vis-à-vis an agenda to prevent some misfortunes in the future.

The University of the Philippines – College of Mass Communication Foundation, Inc. (UP-CMCFI), in partnership with the Philippine Press Institute (PPI) and the Philippine Social Science Council (PSSC), organized the webinar, which featured, not only the lectures of two distinguished speakers but also breakout sessions that engaged participant-attendees in a workshop.

In her opening remarks, CMCFI President and webinar leader Dr. Arminda Santiago emphasized the historical importance of this webinar in that it would feature a workshop to deepen the discussion of and actively involve the participants. This is new, and the aim is to tweak the results of the webinar into something more concrete through the plans and recommendations that the workshop participants will proffer.

Meanwhile, Nickel Asia Corporation Vice President Mr. Jose Bayani Baylon’s message drumbeats the value of the media in society. They should be able to do what they do for the public to get the facts. They should have a safe environment in order to fulfill their role in society.

The Executive Director of the CMCFI, Ms. Rissa Silvestre, followed by giving a bird’s-eye view of what the participants can expect from the webinar.

The webinar then proceeded to the presentation of Mr. Jose Jaime L. Espina, the Chair of the National Union of Journalists of the Philippines (NUJP), a safety trainer and peer supporter, and a journalist for more than 30 years. He tackled the topic Safely Covered: Preparing for Safe Crisis Coverage.

Mr. Espina’s talk concluded with the following statement: “By failing to prepare, you are preparing to fail.” This says it all—a succinct message that applies not only to journalists and media workers but to everyone else as well.

Giving context in his talk, Mr. Espina first defined what “crisis” is, settling on a catch-all definition: a “time of intense difficulty or danger.” And, in a crisis situation, he emphasized four roles that the media normally play: to inform, to communicate, to give early warnings, and to conduct community fora.

He underscored the necessity of preparing and having a Disaster Response Plan (DRP), which should be a workshop-output and which should also involve all stakeholders in one’s own department or office. The DRP’s usefulness lies in people being able to determine whom to call and deploy first and help pre-assign tasks for contingencies.

The speaker advised the audience to prepare for a worst-case scenario, wherein the newsroom may virtually be rendered unreachable. It would be best to possess more than one cellphone, have secured hard drives with critical files, have a list of contacts and have back-up partners, like local universities or colleges, or other news organizations. Back-ups may include Facebook and Twitter or even mobile messaging. For personal safety, he gave the audience a “to-do” list and a set of questions to evaluate the risk situation.

An important item, which everybody should have, is the “go bag” containing the essentials—gadgets, food, clothes, toiletries, radio, batteries and other necessities, including a copy of the emergency plan.

More importantly, something that is good for mental health, Mr. Espina accentuated, is having a good attitude during crises, like embracing stress and trauma as real occupational hazards and not as weaknesses. There should be mutual care among colleagues, awareness of any previous traumatic experience, and constant contact with personnel in the field and their families.

What followed was the presentation of Dir. Red Batario, the Executive Director of the Center for Community Journalism and Development, Inc. (CCJDI) on Journalist Protection in the Time of Disruption and Disinformation.

His talk was prefaced by the current issue on the red-tagging of journalists. He then reminded the audience of the existence of a “Philippine Plan of Action on the Safety of Journalists,” which is based on the “United Nations Plan of Action on the Safety of Journalists” and the “Issue of Impunity.” The Philippine plan promotes the safety and protection of journalists and other media workers and pursues the safeguarding of press freedom. What is unique and impressive about this plan is the process of its development—inclusive, participatory, and multi-stakeholder-driven. The actions, insights, and recommendations from media, government, the academe, and civil society sectors were generated during multi-stakeholder consultations at the regional and national levels. The plan had emerged from dialogues with state security forces, as well as training sessions on journalists’ safety, with the Journalists Safety Association Group (JSAG) providing directions in its completion.

Mr. Batario then discussed the action plan for four flagship areas, namely: a) “Integrity and Professionalism”; b) “Conducive Working Conditions”; c) “Safety and Protection Mechanisms”; d) “Criminal Justice System and Public Information, Journalism Education, and Research.”

Said flagship areas practically cover a whole gamut of safety nets, along with key action points (short-, medium-, and long-term) and ethical standards and professionalism, in the practice of journalism and media work. These also include occupational safety, strengthening the response to attacks and threats, gender sensitivity, the examination of laws like the anti-terrorism law, the prosecution process, and media information literacy.

Open Forum

After both presentations of Chair Espina and Dir. Batario, the Open Forum session ensued with various concerns being raised on the safety of journalists and ably addressed by the speakers. The following were the questions posed in the chat box and Facebook pages of CMCFI, PPI, and PSSC with the respective responses of the speakers:

- On the question of whether or not journalists should be armed, both speakers said that they respect individuals’ rights to arm themselves but they do not promote and encourage gun use because they will be marked as combatants, and both speakers do not want the development of a gun culture. An opposing stand was shared by one of the audience members—that journalists should arm and protect themselves, provided they are educated on when and how to use a gun—as he was of the opinion that journalists should not be sitting ducks.

- The second question was about some editors being oblivious as to the safety and care of journalists involved in risky coverage. The speakers said that concern for personal safety is valid and should be considered.

- The next question was about safety from red-tagging. Accordingly, there is no one answer to this, but journalists should ensure the integrity and accuracy of their stories and should gain the trust of the citizens. They should also coordinate with human rights groups and have a united front against red-tagging.

- The fourth question was about ways of strengthening Media Information Literacy (MIL). There should be focus on integrating journalism courses in the academe, but this should go beyond schools. It should also trickle down to common folks who read newspapers and watch or listen to the news.

- The last point was not a question but a comment to always maintain ethical standards in writing.

Workshop

After the Open Forum, the webinar proceeded to its high point—the workshop, with 27 participants divided into two groups. These workshop participants came from PPI’s members, who represent community newspapers, radio stations, the print sector, and other platforms nationwide.

Under the supervision of two seasoned facilitators, namely, CMC Associate Dean Dr. Rachel Khan and CMC Journalism Department Chair Lynda Garcia, each group of participants discussed the following questions posed by the speakers:

- Chair Espina:

- Have you covered a crisis? Please share your experience on how you prepared and how your newsroom supported you.

- Check your phonebooks. Do you have one? How many emergency numbers are stored in your phonebook?

- Do you know at least two of your editors who live closes to your newsrooms? How close are they?

- Director Batario:

- What is the biggest threat facing you today as a journalist?

- How can you and the journalism community address that threat?

The workshop results were subsequently presented in the plenary as follows:

Group 1: Director Batario and Chair Garcia

Have you covered a crisis? Please share your experience on how you prepared and how your newsroom supported you.

| Crisis | Preparation | Newsroom Support | |

| Participant 1 | Typhoon Rolly | Approached LGUs, prepared a go bag | Logistics, food, equipment |

| Participant 2 | – | Not prepared | – |

| Participant 3 | Typhoon Peping (2008), Typhoon Cosme (2012) |

Peping: Waited for the water level to subside to a manageable level Cosme: Preparation was possible because of PAGASA reports; proper equipment were brought |

Moral support |

| Participant 4 | Earthquakes in Mindanao | Apart from duck, cover, and hold, not much preparation given the unexpected nature of earthquakes | Monitored safety through frequent calls |

Check your phonebooks. Do you have one? How many emergency numbers are stored in your phonebook?

| Emergency Contacts | |

| Participant 1 | 48 municipal and city police stations, 5 DRRMOs, father |

| Participant 2 | 1 provincial government, 3 police stations, 2 DRRMOs |

| Participant 3 | 14 provincial hospitals |

| Participant 4 | 50 municipal police stations, NGCP, MDRRMC |

| Participant 5 | district police stations in Metro Manila, hospitals NDRRMC, Red Cross, MMDA, wife |

Do you know at least two of your editors who live closes to your newsrooms? How close are they?

Two participants responded affirmatively, with the closest editors living approximately 15 and 30 minutes from their newsrooms.

Group 2: Chair Espina and Dr. Khan

What is the biggest threat facing you today as a journalist?

The group pointed out that the threats to journalists are not limited to physical danger due to coverage. Nonphysical threats include:

- Lack of job security – Many lost their jobs during this period due to the lack of sustainability of print media during the pandemic and the closure of ABS-CBN, which affected correspondents in the provinces.

- Lack of transparency of the government, especially LGUs

- Threats by politicians, especially in the form of libel charges

- Mental health problems and trauma from covering the pandemic and disasters

- Disinformation and how the media themselves are sometimes misled, especially during disasters

- Lack of logistical support from the community and the government, especially in terms of the sustainability of media establishments

How can you and the journalism community address that threat?

The group suggested community action in the form of the following:

- There is a need for journalists to learn how to protect themselves.

- Fact-checking should be a practice among journalists, not just official fact-checkers. Journalists should not let our guard down even when the news comes from their inner circle as they can also fall victim to false information.

- There is a need to assess what newsrooms are doing for their staff in terms of protection (e.g., PPEs in covering the pandemic, hazard pay, protection from harassment by the powers-that-be).

- There should be constant sharing (of experiences and best practices) and support from the media community, especially when one is facing threats. Webinars like this help keep community journalists informed of the situations of their fellow journalists.

The webinar then ended with the closing remarks of Dr. Elena Pernia, Vice President for Public Affairs of the UP System and former Dean of the College of Mass Communication.